WonderBuhle - COMFORT

28 November 2020 - 06 February 2021

Wonder Buhle: If they dont see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black

By - Lindokuhle Nkosi

Wonder Buhle Mbambo is a South African visual artist from kwaNgcolosi in Kwazulu-Natal. Born in 1989, Mbambo’s received his formal training in 2010 at the BAT Centre, which co-ordinates a visual arts residency in Durban. He studied Fine Art, under the mentorship of Themba Shibase at the Velobala Apprenticeship Program at the Durban University of Technology (2011-2013). In 2016, Mbambo was the recipient of Bremer Kunststipenium Art Grant. Towards the end of 2020, BKhz Gallery hosted Mbambo’s solo exhibition, titled Comfort, at their Braamfontein location. In the days preceding the show’s opening, Lindokuhle Nkosi and Wonder Buhle Mbambo spoke the the show, its title and the ways in which “comfort” may signify something than the ease and copacetic nature we understand it to be.

*

What is more endless than the sky and our ambitions for staying live? Us, the wretched of the earth from birth. Conceived into a structure set out to kill us. For whom else is life optional… future projections the stuff of science fiction? Dystopian dynasties based on every day lived experience? “Black history is black horror”. And black love, a thing of resistance and revolution.

“If they dont see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black.”

*

There is always more. There is always enough. Or in the words of Wonder Buhle Mbambo; “Angihluphekile. Angixakekile”. These words refer a work produced for the artist’s latest show, Comfort, which opened at BKhz in December, and perhaps best explains the name of the exhibition. The artist tells the story of his grandfather, who after losing his job and falling on thornier times, never lost his composure, the ease with which he approached life. “Umkhulu after engesasebenzi , things went a bit sour edladleni 4 but he didn’t want people to think that we were poor. We had food. We had clothes. So he always said; “asihluphekile. Sixakekile.” A reminder that they were not what they were going through. The situation was circumstantial. A matter of white supremacy, capitalism, fate, geography. Who they were at the core of them however, would remain unchanged. Wonder remixed this into a protective spell of sorts. “Even when there are troubles, we will remain untroubled”. The painting features three figures locked in the centre of the frame, the one in the middle hoists the other two up on his arms, on either side of him. It feels convivial. There is love here. Care. Overlaid with Wonder’s signature star-flowers, the blues on their tshirts become the blue of the backdrop they float against. The figure in the middle, his head abruptly chopped in half becomes both the foreground and background, expanding outside of himself into the ether. The star-flowers painted onto their faces work to protect them, but also obscure their identities. “I always try to give people a real painting, with multiple layers, before charge the bodies with these flowers. However, I kind of like that it’s hides their identities a bit when I play around with the symbol, especially on faces. The flowers are a symbol of protection. They become a shield,” explains the artist. “The boy’s head disappears into the sky… it’s a symbol of infinity. An endless knowledge. An endless spaces of possibilities. The figure in the middle, the one who’s carrying the other two, he’s the guy with the whole knowledge that he now has to pass on.”

*

“Move your bloody face next to mine and rub me with it. We are dying from so many stories. We are not complete in the mind from so many stories of burning houses, missing children, slaughtered animals. Who will put the stories back together and who will restore the bodies?”- Daniel Borzutzky, Memories of my overdevelopment 6

All of Wonder’s images are overlaid with a white star-flower figure. There’s an image, and then the image on top of the image, another layer of interpretation. Growing up in KwaNgcolosi, 41kms from Durban and on the banks on the Inanda Dam, Wonder was raised by his mother, a sangoma and his grandmother. “I grew up without sibling. I was the only child,” he explains. “So if something happened to me in the streets, I had to know how to defend myself. My grandmother helped me build my confidence. Not just to defend myself, but to advocate for myself.” Growing up in this rural setting, he found himself playing outside, often chided by his grandmother to be cautious. “Ungadlali lapho,” she would say, steering him away from a patch of land sprouting white flowers. “Imbali zami zenhlanhla lezo.” He didn’t question it at the time, accepting it with the innocence of youth, but later, after the passing of his grandmother, and as he began to experiment with his artistry, the flowers would make a prominent return to his life. “I started to think about what fortune these flowers carry,” he says. “I took the image of those flowers, and took the small yellow flowers that grow on imphepho, and stars, and fused them into a symbol that could purify the figures that I paint. To give them a sense of guidance. Protection.” In a way, this star-flower overlay that coats all of his work is a mosaic or portmanteau comprised of the things a younger Wonder relied on for safety. The white flowers – his grandmother. The imphepho flowers – his sangoma mother. The stars – solid and unchanging in the vast and endless KwaNgcolosi sky.

*

“Be who you are and will be. Learn to cherish that boisterous black Angel that drives you up one day, and down another protecting the place where your power rises, running like hot blood from the same source, as your pain.

When you are hungry learn to eat whatever sustains you until morning but do not be misled by details simply because you live them.

Do not let your head deny your hands any memory of what passes through them.

Not your eyes nor your heart.

Everything can be used except what is wasteful (you will need to remember this when you are accused of destruction.)

Even when they are dangerous examine the heart of those machines you hate before you discard them and never mourn the lack of their power lest you be condemned to relive them.

If you do not learn to hate you will never be lonely enough to love easily nor will you always be brave although it does not grow any easier. – Audre Lorde, For Each Of You.

*

“One thing [my mother] pointed out, which was very powerful, was a snake I had begun to use in my work. I did a sketch, but I wasn’t really thinking about it. It was just a random feeling. Many people associate snakes with negative things and I was just wondering what else can be found there. What other meanings.”

“I painted this piece with a snake and [my mother] came into the studio. She commented, ‘Ha! Umonyo lo.” She explained that umonyo inyoka yenhlanhla . When you come across it, you don’t mention the sighting to anyone. That silence will reward you with good fortune.”

“It would seem the very denial of dreaming that society seems to impose on black folks, while it hasn’t made us dream less, does seem to punish us for what dreams we do have.”- Kevin Young, The Grey Album

*

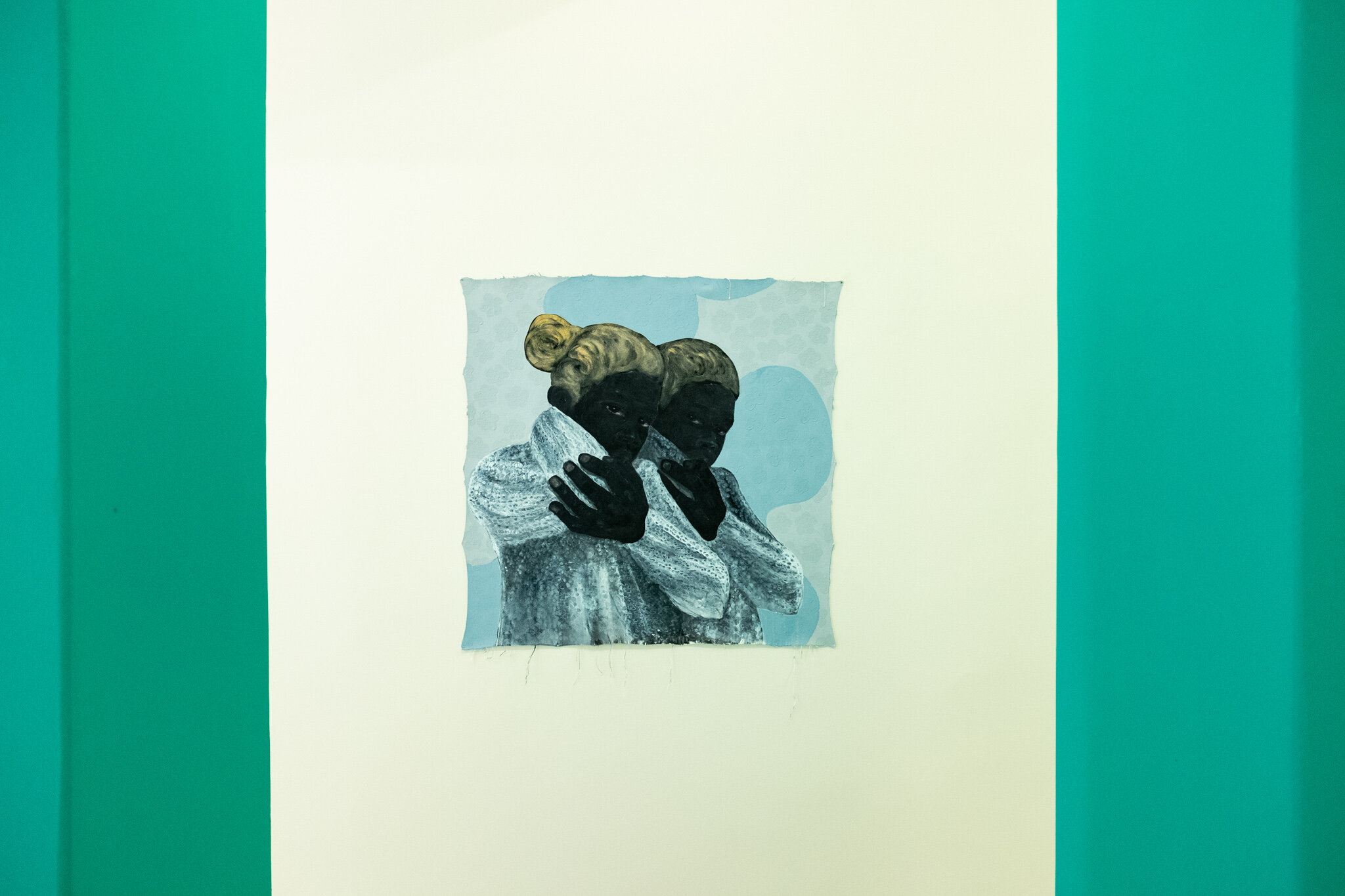

Another painting. “Umvikeli”. Two men seated/standing back-to-back against a royal burnt gold background. They reach backwards to embrace one another, the black of their hair becoming one. “It’s the outer you and the inner you,” Wonder speaks through his paintings with an intimate knowledge of every layer of charcoal, acrylic. Everything is deliberate, even that which is not. His blacks he draws from the depths of the Inanda Dam. His golds, from a dream he had, where the ocean spat nuggets of the rarefied element at his feet. “The outer is the face that we show when we think we’re in danger. It protects. It’s hard but on the inside, is a fragile, vulnerable person. This is about showing the textures of comfort.”

By “textures’, I understand him to mean negotiations. The concessions one must make to maintain some part of them soft. The things we have become accustomed to that we shouldn’t. In “Umvikeli”, the outer figure has two spears lodged in his face, four in the torso. Resembling a nativised tarot card, “Umvikeli” would be the “Six of Swords”. Minor Arcana, when pulled reversed, the card can signify feeling of stuckness, lack of progress, progress that does not matter, unanticipated change or unwanted results. Pulled upright, as in the painting, it can represent a necessary rite of passage, a move towards calmer waters, the presence of spirit guides and guidance, and a regretful but necessary move in more positive direction. “I was also drawing on the idea of martyrdom,” he says. “Someone who believes in something so much, they’re willing to sacrifice their lives for it.”

Bio: Lindokuhle Nkosi is a writer/editor from South Africa whose textual work often merges with installation and performance. She completed her MA in Creative Writing with Rhodes University, using the black imaginary as a tool to investigate the mechanisms of violence in a hyper-violent societies, and how this impacts black livelihoods, cultural produce and the black, femme imaginary.