Investec Cape Town Art Fair 2023

BKhz gallery had the pleasure of hosting three different booths at the 2023 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Talia Ramkilawan at the Tommorow’s / Today section

Zandile Tshabalala at the Main Booth section.

Lunga Ntila at the Solo section.

Talia Ramkilawan - Looking at the same moon

Talia Ramkilawan wants us to look at the moon.

by Dinika Govender

Not because it represents the axis around which her family’s Tamil roots and rites turn. Not because – at the time of writing – the waning moon is in its ‘disseminating phase’. Not because it happens to be in Scorpio either.

Although she might invite us to do with these facts what we will, she is in a state of dissemination of her own: shedding our gaze in favour of something more vulnerable, more accepting, and less concerned with the urge to turn the everyday into discourse.

In this latest series, “Looking at the same moon”, Cape Town-based artist Talia builds on an ongoing and distinctive body of work that serves as a personal exercise in both reckoning and healing: needling through her relationships with self, family, friends, lovers, queerness, South African Indian-ness, indenture, and a chain of social and historical complexities that follows.

This time, however, she stops to look at herself in the moment – not as a precursor to a cooler/smarter/hotter self, or as physical evidence of a series of unfortunate events, or a data-point on an unsolicited census.

“My life has seen a lot of change over the past few months, but no matter how I’m feeling, how hard things are, or how amazing things are, I am still me,” she explains. In response, Talia zones in on the small moments that ground her in “Looking at the Same Moon”: a messy bedside table, a moment of self-indulgence, an existential echo in a family photograph and more.

In “Pleasure Has Made Me More Resilient, Regardless”, for starters, a golden locket implies the existence of hardship in the artist’s life, while stressing a clear persistence. We get the idea that it is less about serving up personal pain in order to triumph over it, but more about actively identifying less with hardship itself as an equally valid form of experiencing and choosing pleasure.

Talia affirms as much: these are meditations on remembering to “choose to feel good.”

“How am I propelling myself forward rather than stagnating in pain? Pleasure propels me forward. It keeps me going for much longer, whereas pain is just heavy and hard. It slows me down,” she explains – unwittingly negating the trope of ‘the tortured artist’ that the creative industry all-too readily exploits.

This negation of external expectation, paired with her commitment to sharing her feelings while she is sitting in them, is what makes this new series taut with unflinching honesty.

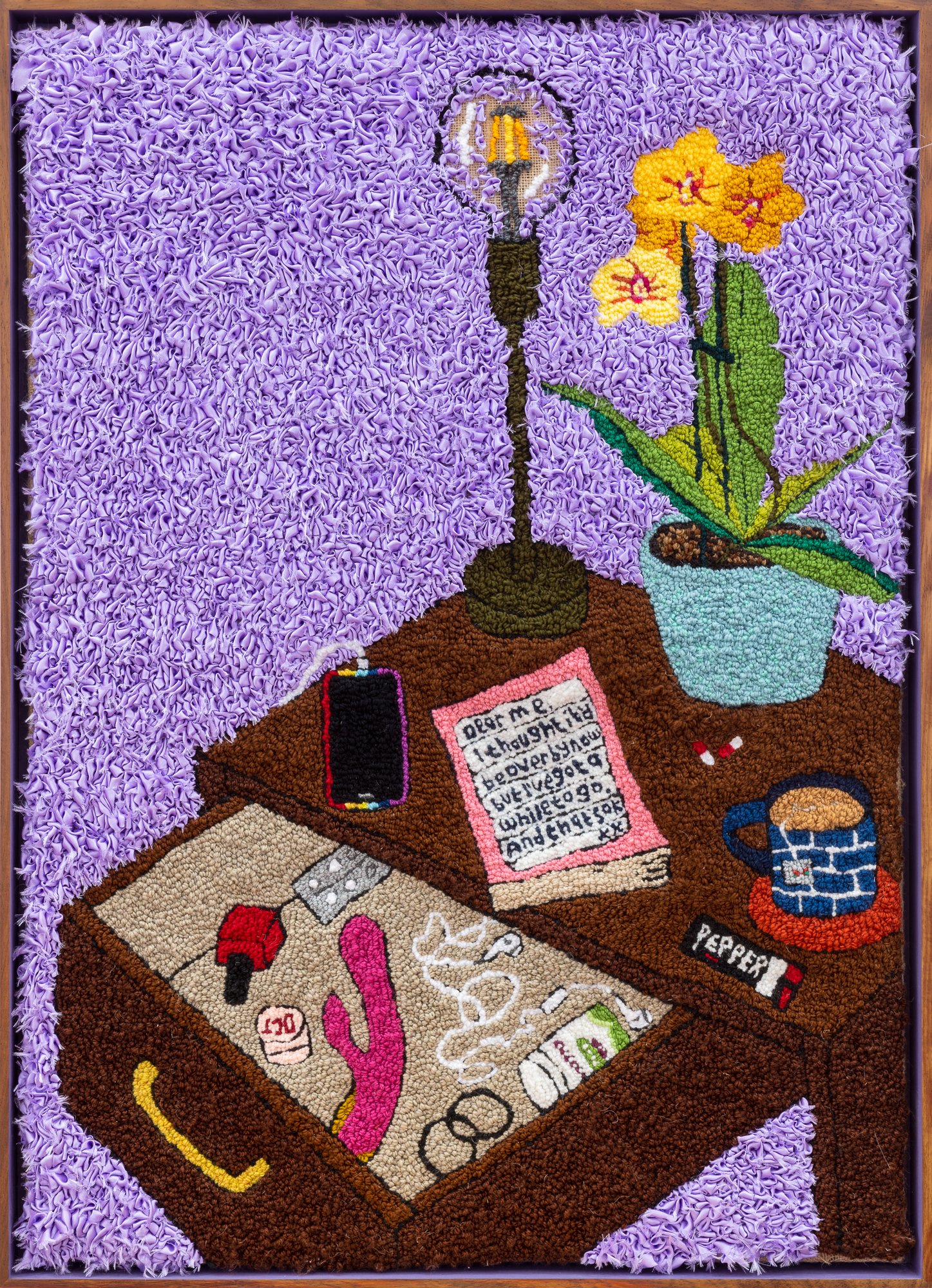

“State of Mind” shows us a still-life of a bedside table littered with everyday necessities – some mundane (phone, plant earphones, tea) – others more telling (dildo, DCT, pills, pepper spray). For

Talia, this was a moment of reckoning with the fact that there is a version of her ordinarily organised, tidy self that’s gotten untidy lately. The only clue as to what might be behind this ‘state’ is a note written to herself in the piece that reads: “Dear me, I thought it’d be over by now but I’ve got a while to go. And that’s ok. xx”

Here the message is felt: it’s not about why. It’s about the fact that it, this moment, exists.

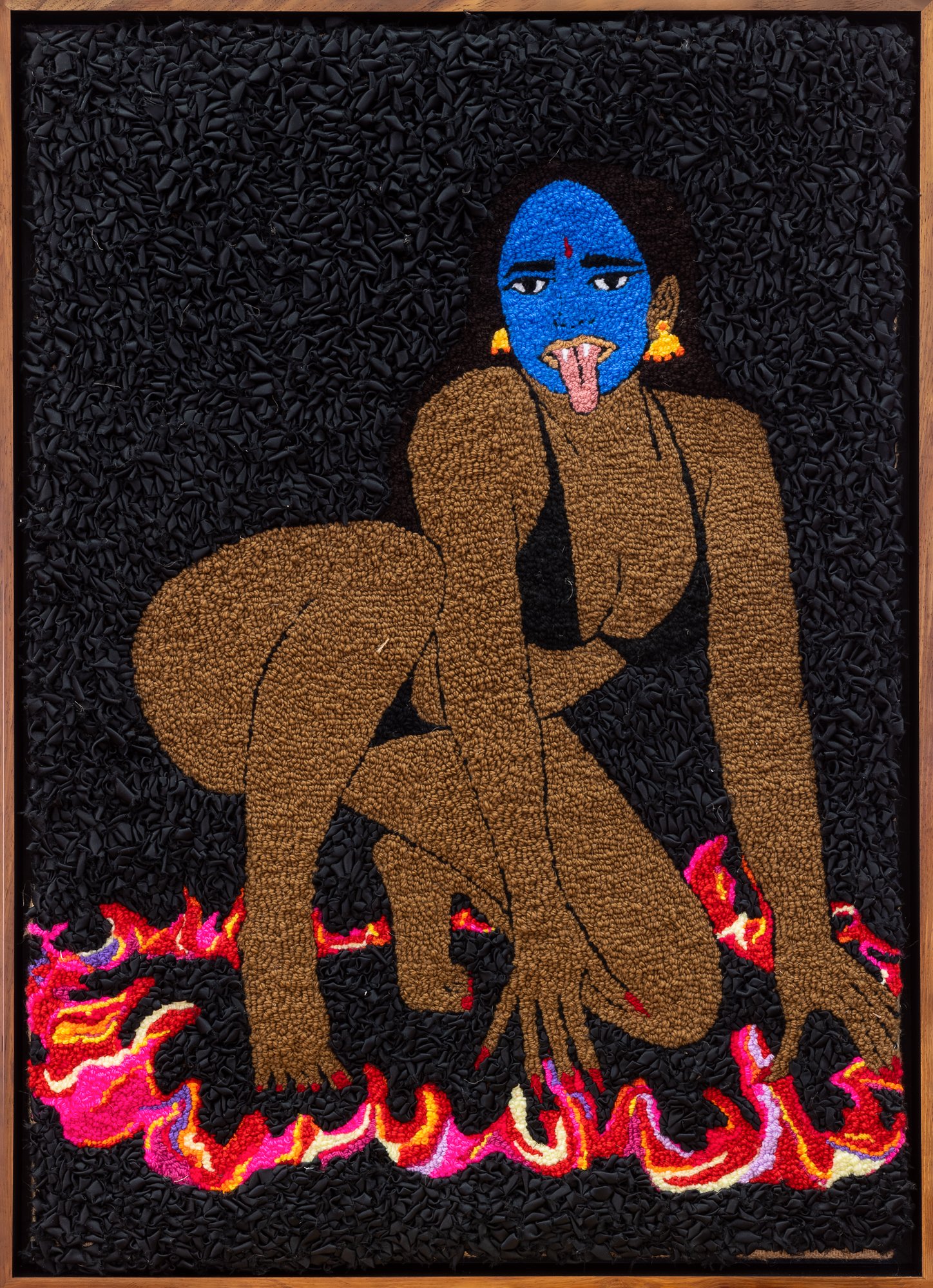

In sharp contrast, “Love Me Harder” is an expression of the primal, all-consuming energy that follows what we imagine to be a fallout in love, or the sparks of something new. While the title hints at a sense of defiance, the image of a bikini-clad woman crouched in a ring of fire with the face of Kali — the Hindu goddess of ultimate power, destruction and creation — suggests something more complicated. For all her wildness, is there also a sense of entrapment, of fear? Or is it a thrill of anticipation, of sudden liberation?

Her direct gaze implicates us, but says no more.

From the feral to the familial, “Wedding Day” offers a seemingly divergent moment of reflection. Drawing on an old photograph of her grandmother on her wedding day, flanked by her grandmother’s mother and mother-in-law, the three women gaze out with eyes half-open — a tad indifferent, but no less dutiful — as if to say ‘If you must.’

But before we can get too lost in projecting ideas of brown families, gendered experiences, and happy-ever-afters onto “Wedding Day”, a woven nude selfie comes into view to remind us that this is Talia’s moment. We are mere guests.

“Thinking If You Also Dream of Me” shows a topless Talia snapping a nude in a rainbow-flag encased phone, adorned with gold jewellery, long red nails, red bindi, and solo-disco appropriate headphones. Draped by indoor plants above her, body poised as if to say ‘Felt cute, might immortalise later,’ this nude is a clear departure from a similar autobiographical piece made in 2020 titled, “You’re Hot for an Indian Girl.”

That’s because it is an intentional departure: from making work that responds to perceptions of her, to making work for herself and “not for anyone else.” “I take nudes just for myself and they go nowhere. I think it’s really special to feel sexy for yourself,” she says.

In this case, we should all be so lucky – inspired even.

In piecing a handful of these everyday intimacies together and leaning into the little pleasures that move her “forward in a lighter way”, Talia unwittingly builds a mirror in time, encourages herself to look at it with non-judgemental, self-affirming eyes, and invites us to do the same.

“Who are we in our most vulnerable and intimate moments – in our moments of pleasure, friendship, love and heartbreak?” she asks.

Just like the moon is the moon is still the moon in all its phases – from new and unseeable, to full and unavoidable – “Looking At The Same Moon” reminds us that we are worthy of being here: in frame, as is, in each phase and every cycle of our own becoming.

<3

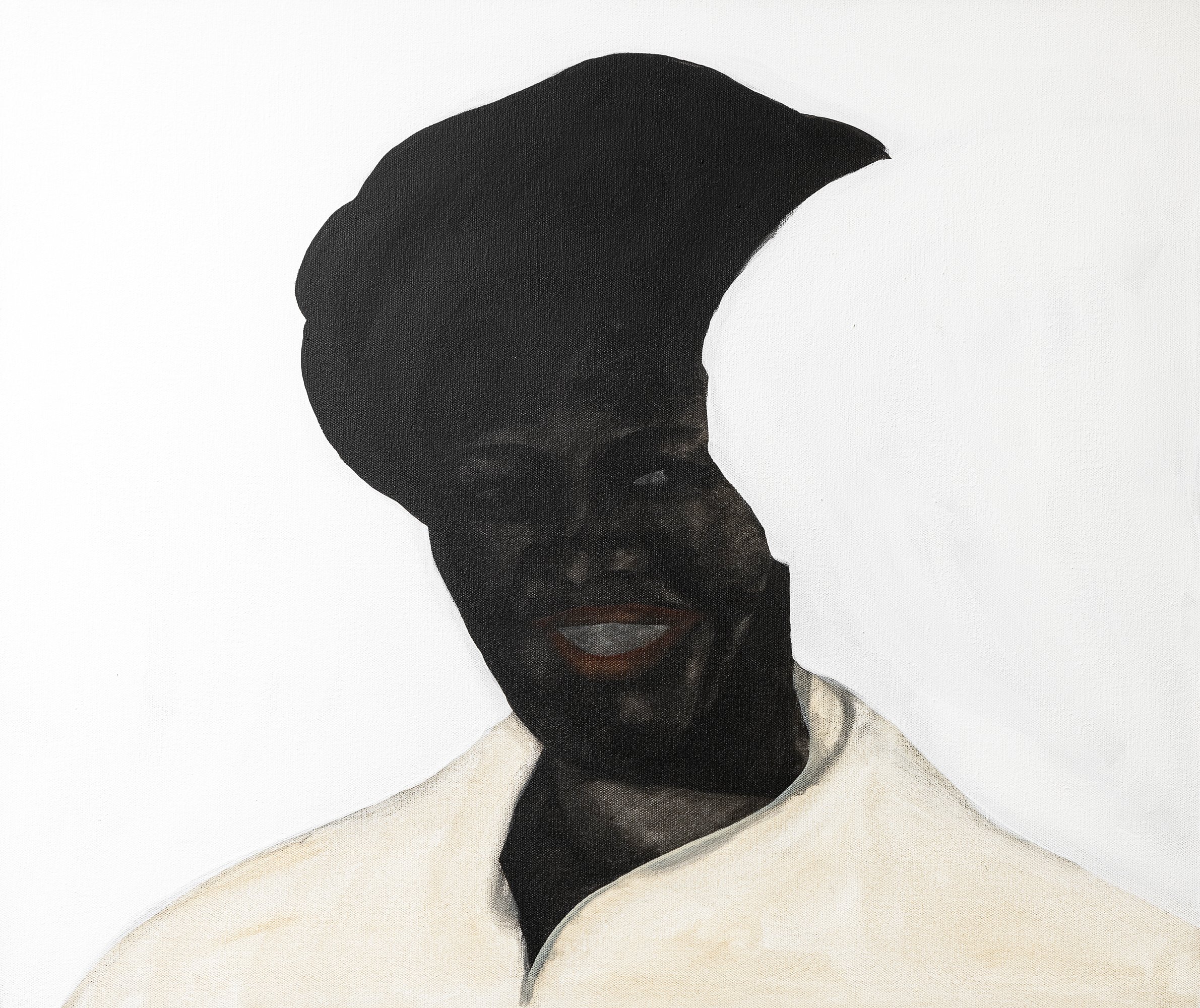

Zandile Tshabalala - Umcimbi

Come party because ‘hard times require furious dancing'

by Fikile Mali

Dearly Beloved

You are cordially invited to participate as we contemplate the twenty first birthday.

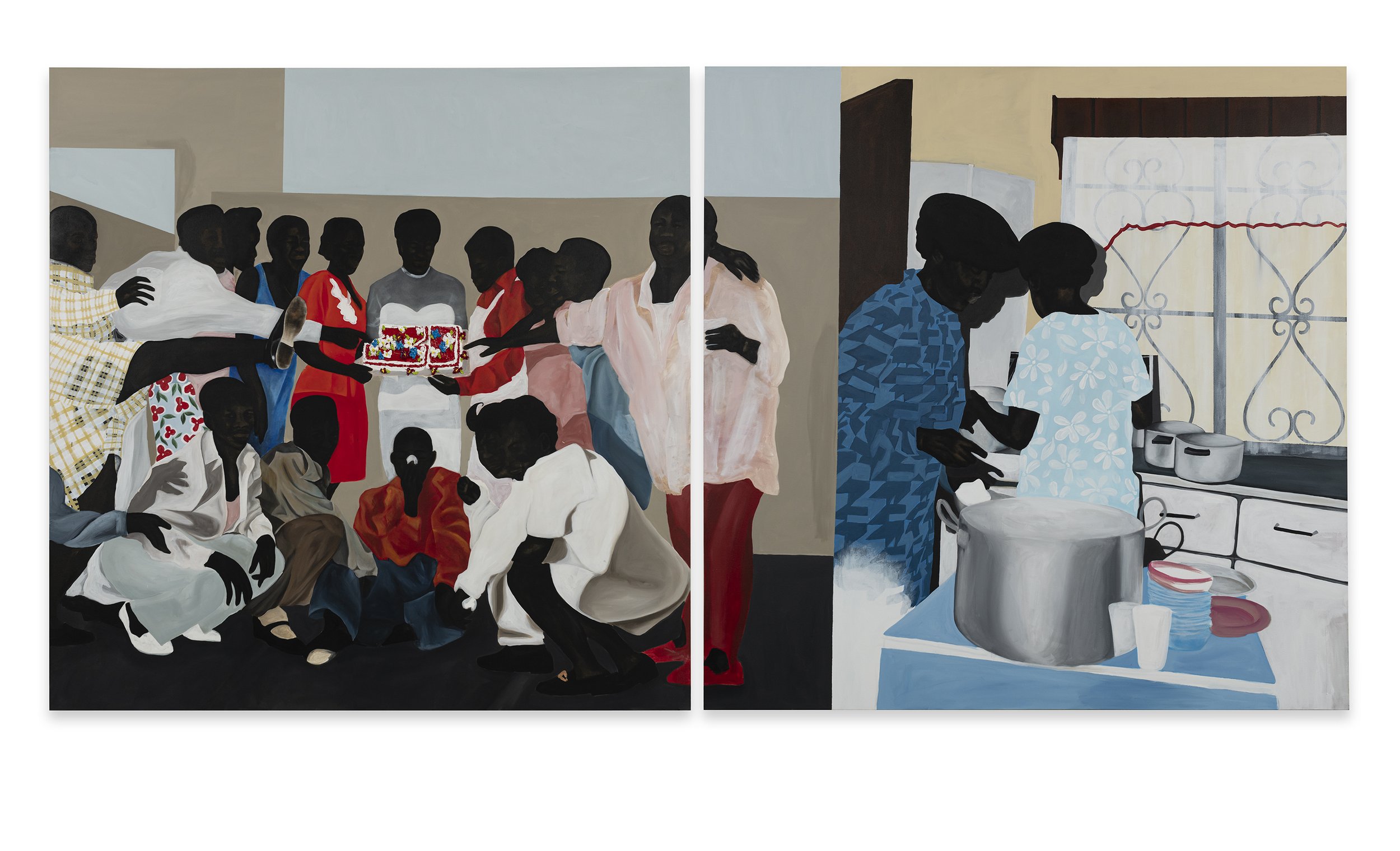

A commonplace rite of passage where the celebrant often receives a Key to Freedom, the twenty-first birthday signifies entry into adulthood and with it,the agency to forge an independent path. A conferring of trust by other adults, in Zandile Tshabalala's presentation the twenty-first birthday is a site to examine and imagine gathering in the name of supporting the growing Black femme as she comes into her agency and growth.

In her own words, Tshabalala's practice is an urgent and incessant response to the zeitgeist because, "That’s what we need, especially in painting history. We need a depiction of Black women in different angles and not just this one story as it has been told throughout painting history."

Centred around and informed by Black women, Tshabalala’s practice can be read as a soft confrontation; calling her audiences to take part as she contributes towards reconfiguring the global norm that endorses the erasing, censoring, fetishising, sidelining, and vilification of Black women. Prioritising their joy, rest and revelry, Tshabalala’s figurations invite audiences to consider the ways they perceive Black women.

Lending itself to what would be a contemporary blend of post-impressionism and fauvism, Tshabalala's style places emphasis on emotion, painterly qualities and colours with the function of fabulating existing scenes.

While developing her painterly prose and practice, Tshabalala also admits to understanding the need to platform varying perspectives. "It started with the community of self but now there’s intimate partners, friendships, family. I think with a lot of my practice right now, that is the enquiry. How do I document these relationships? How do I archive these memories and experiences?"

Like her presentation at the Kunstmuseum Magdeburg entitled In Search of My Mother's Garden, Umcimbi expands on Tshabalala's study of community and fellowship with the twenty-first birthday as its backdrop. Giving off a granular, nostalgic feel, similar to that of disposable film photographs, the works featured in Umcimbi act as speculative fiction additions to the family archive her work often referencs. Continuing her efforts to address and undermine the apathetic gaze Black femmes are subjected to, Umcimbi picks up where In Search of My Mother’s Garden left off, adding depth to the context, people and interiority she first introduced in 2022.

On presenting a festive moment to defy the norm, Umcimbi brings up educator, researcher and vinyl collector and selector Nombuso Mathibela’s throughs on the concept of groove being revolutionary: “If we truly believe that freedom is a practice, some sort of daily exercise, then how people choose to express themselves is pure politics. I really believe in what Alice Walker calls holding the line of beauty, form and beat. Hard times require furious dancing. And that dancing at some point is something that we learn to be very basic for maintaining balance.”

Forming part of a genre of figuration where Black women’s personal empowerment, experience and agency supports their efforts to transcend and reject the distorted Western constructs of their lived femmehood, Tshabalala’s subjects are accomplished, loved, sexy, critical, unbothered softies. Decked out in material and political luxuries like fur coats, time, space, community, resolve, and healing, their reality succeeds ours.

So, come.

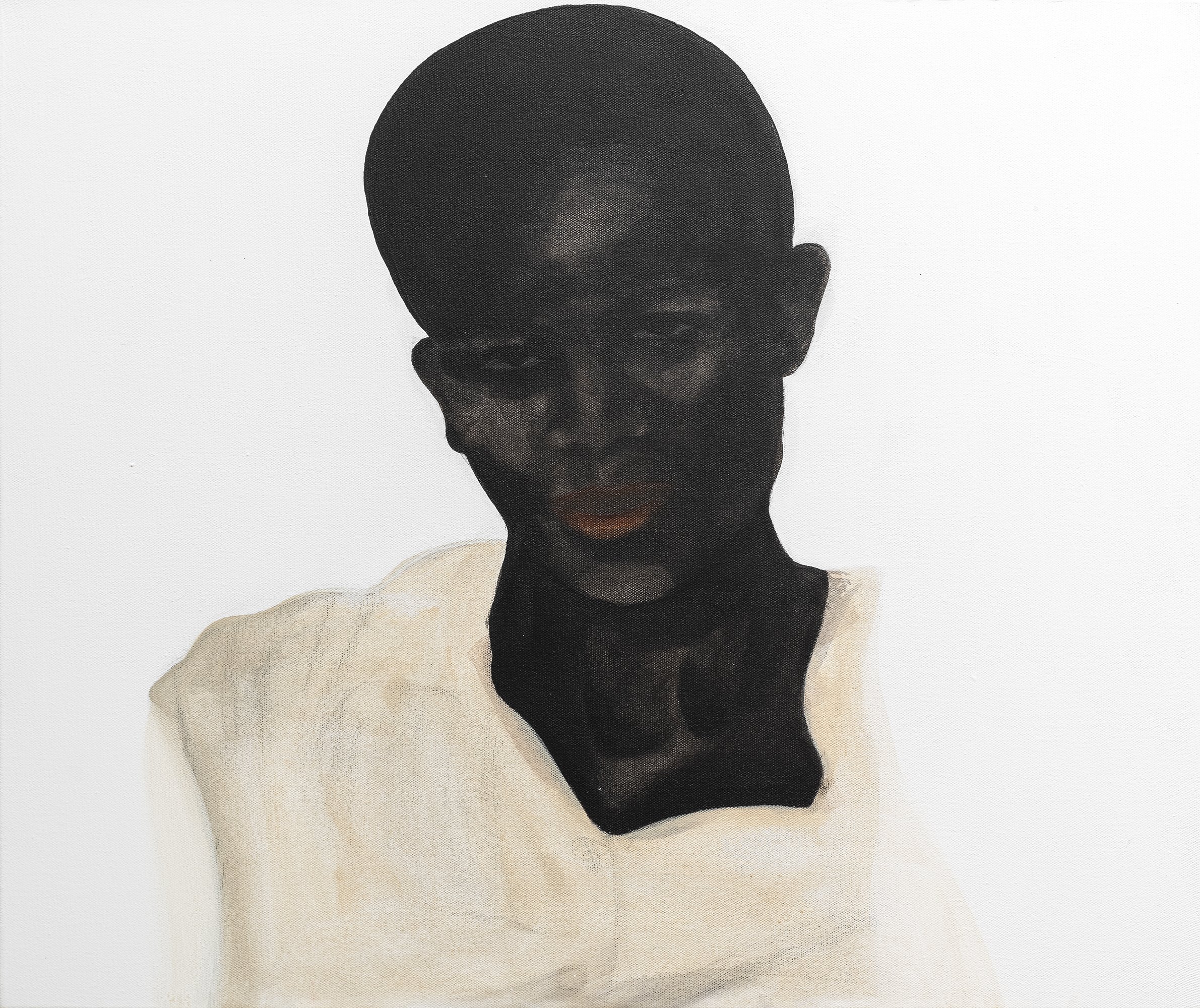

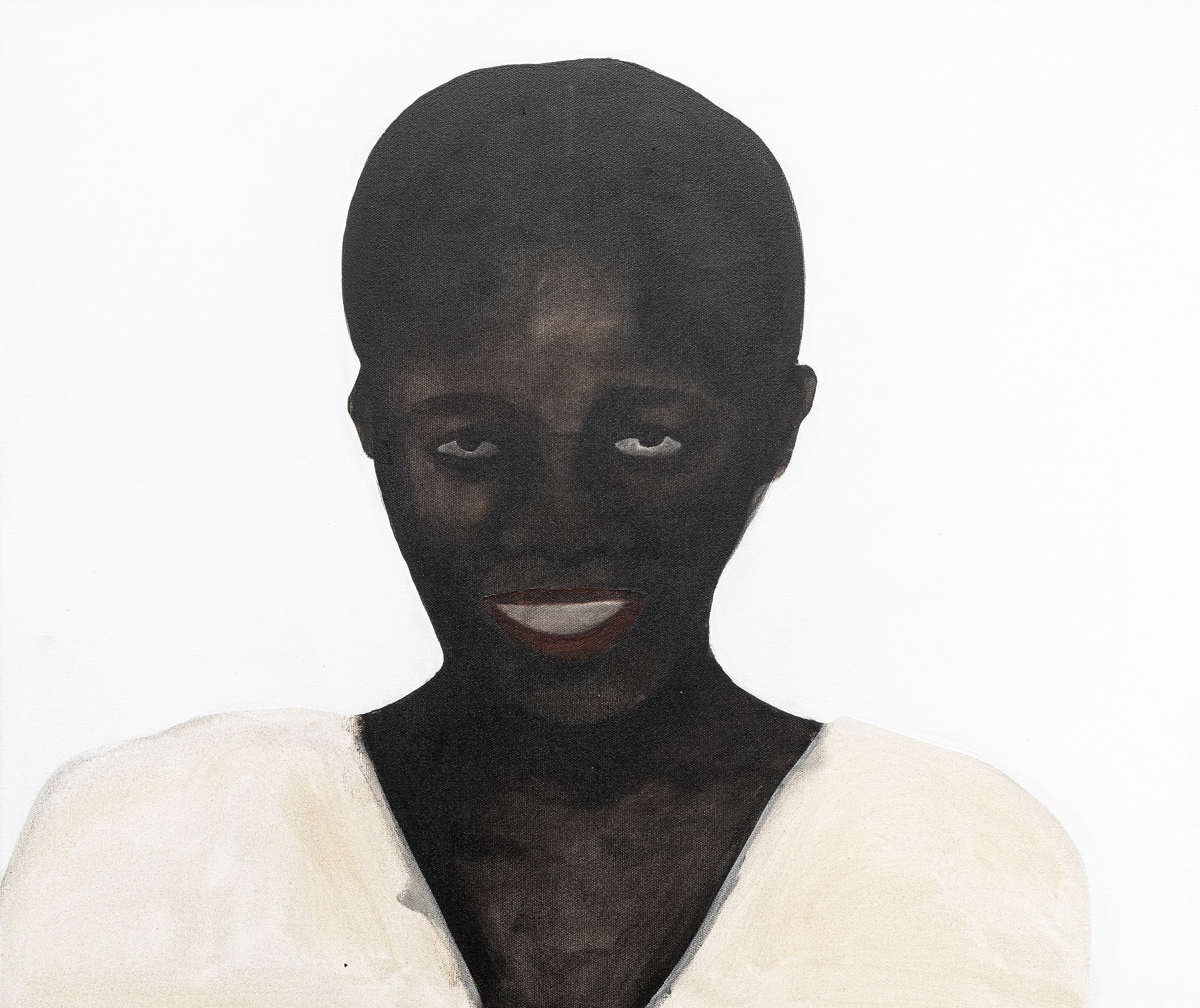

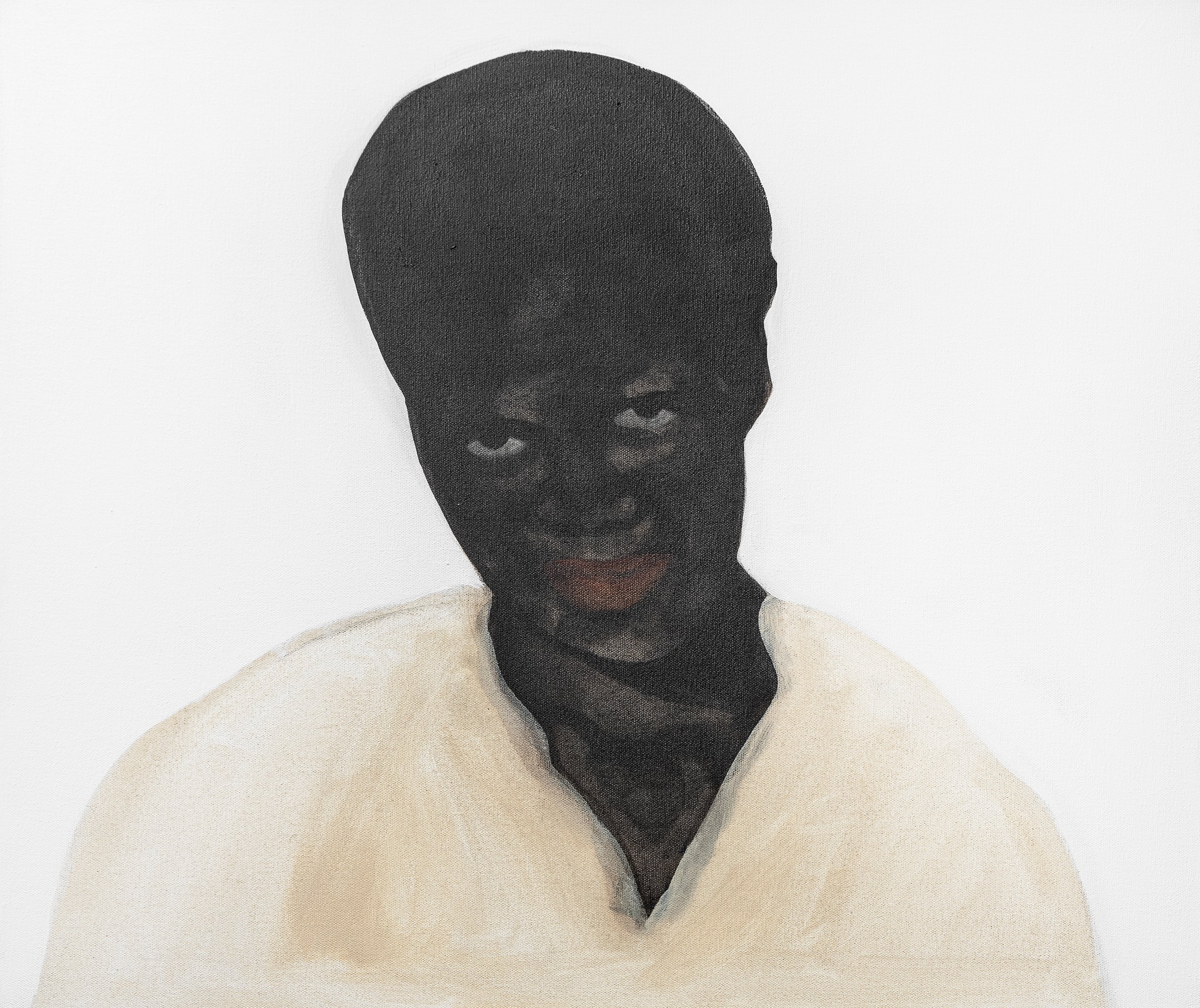

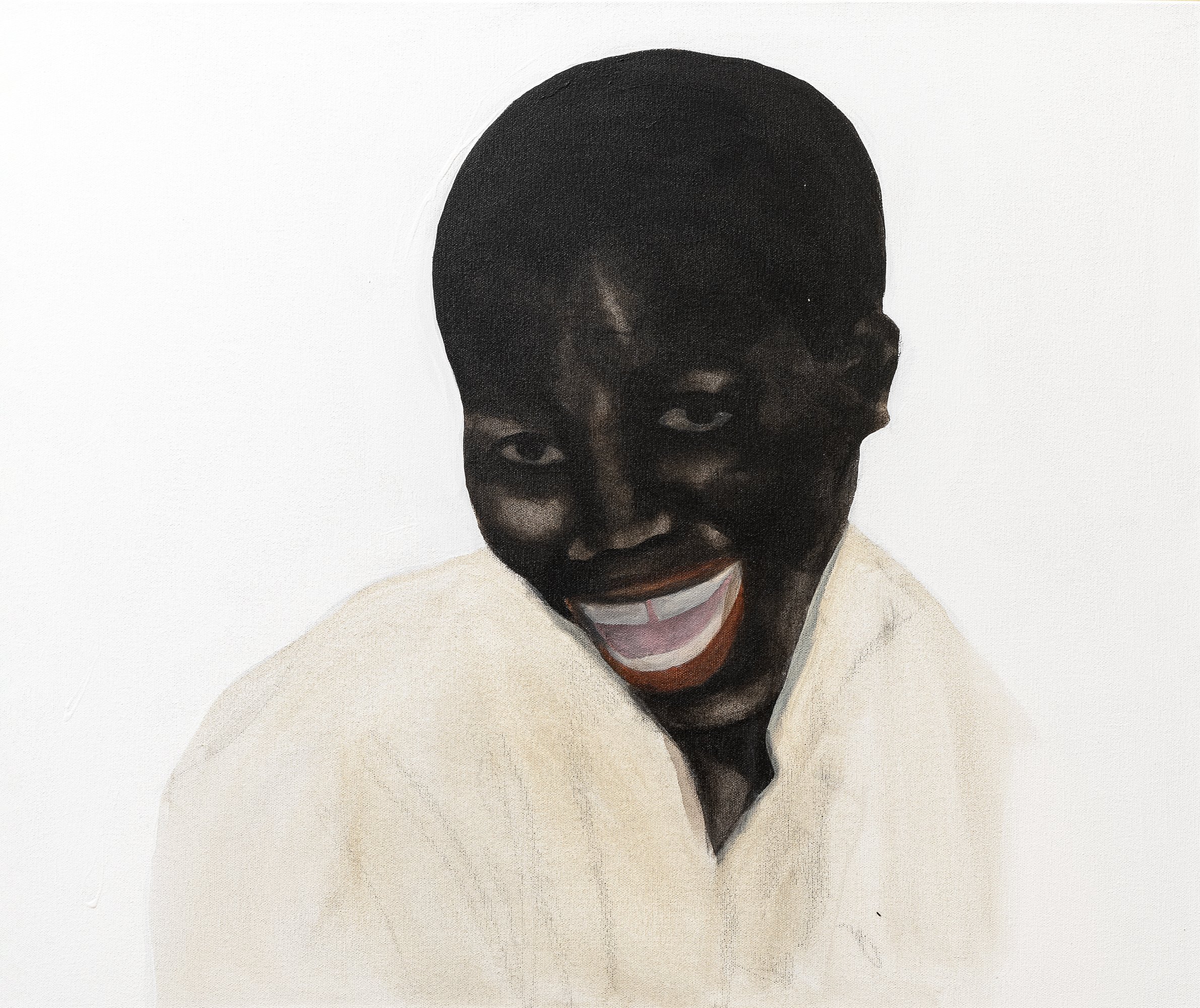

Lunga Ntila

“Jwale Modimo wa re: Sebaka ha se be teng mahareng a metsi, mme se arohanye metsi le metsi.”

– (Genese 1:6)

They had their reasons, but you can’t keep things like us folded for too long, the creases can’t hold. I know you’ve felt the seams bursting, too, how much it hurts, how terrifying it is because we know how terrifying we are, they must have folded us for a reason, we’re going to hurt the humans if we expand fully, we’re going to burn everyone we care about, we burn too bright, it’s not safe to exist, we’re dangerous, we’re dangerous, we’re dangerous!”

– Akwaeke Emezi, “Deity | Dear Eloghosa” Dear Senthuran

A figure appears, seated.

In their left hand, rising blackly and gripped staff-like is a white flower, circled asymmetrically by three oversized bees. The image is a variegated feast of texture & ornament: of cloth, leather, petal, skin, metal and beads – at once stratified and superbly integrated. Both one and many.

The figure’s face unfolds and gently explodes kaleidoscopically, a striking feature that comprises the bedrock of Lunga Ntila’s now unmistakable style. Notable here are the eyes, always challenging any conception of a unidirectional gaze, and of course, Ntila’s pointed use of colour. Red rises above the figure’s many-eyed, many-lipped, obsidian-charcoal face(s).

by Maneo Mohale