Hayani

Mashudu Nevhutalu

09 Dec 2023 - 23 Jan 2024

(closed for holidays between 17 Dec - 7 Jan)

Reading Hayani as an enquiry into the institution of belonging

Zaza Hlalethwa

This show was going to be called Home. But in contexts, like South Africa, where folk perpetually seek belonging because displacement is standard, the generalisation of the anglophone term has diluted the institutional charge that it has in languages indigenous to the region. "I use the word home in reference to the space that I live in. But that isn't home, home," offers Mashudu Nevhutalu as the conversation about his solo exhibition begins to unfold. Perhaps how bell hooks describes love in Communion: The Female Search for Love, when spoken of as an institution, home can be understood as a non-spatial concept that generates the reception and dissemination of care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect and trust.

More than four brick walls under a roof, here home involves a nuanced nurturing that affirms while it enables growth. To transcend the generic, everyday understanding of home, Nevhutalu says, "Translating it to my home language made more sense."

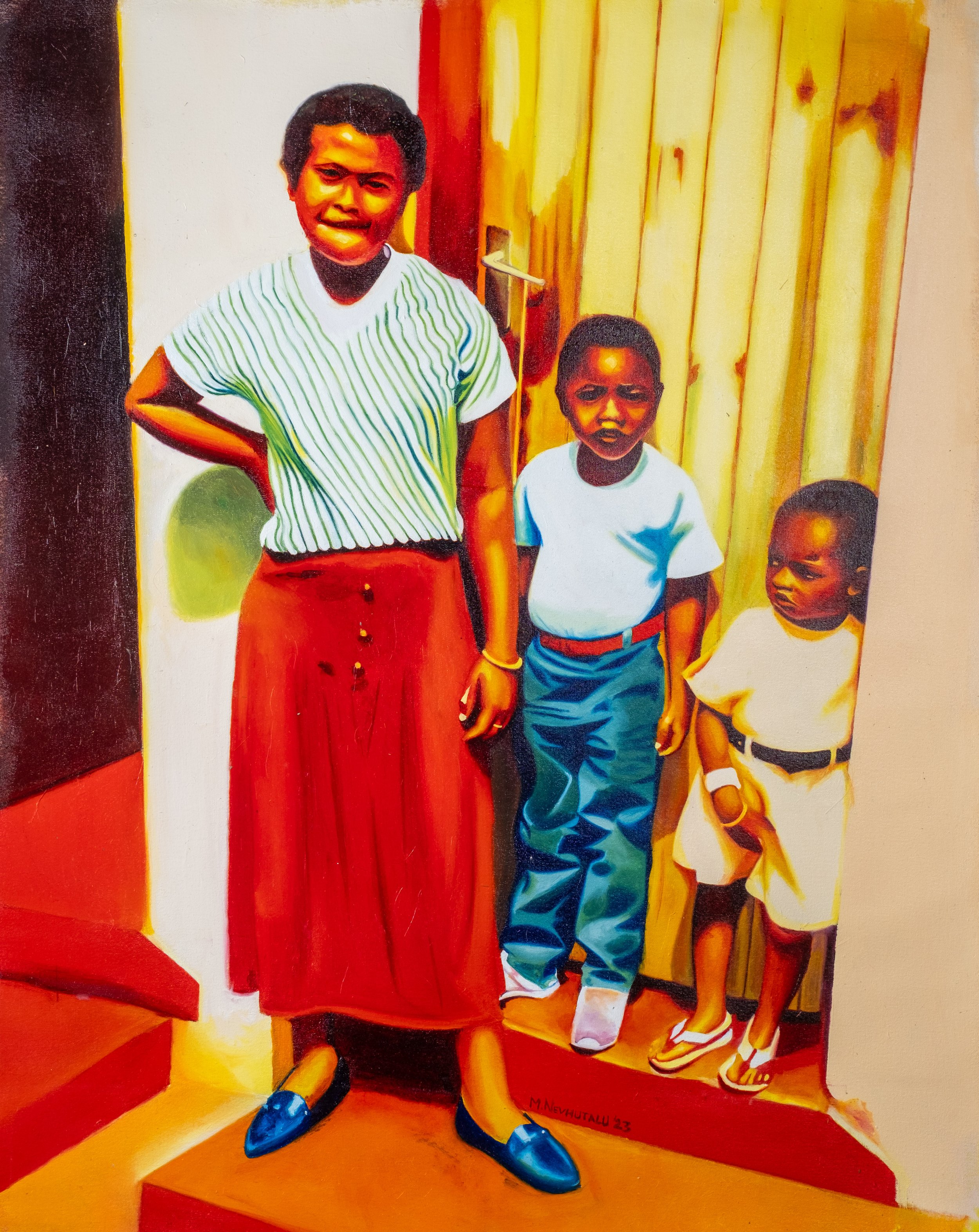

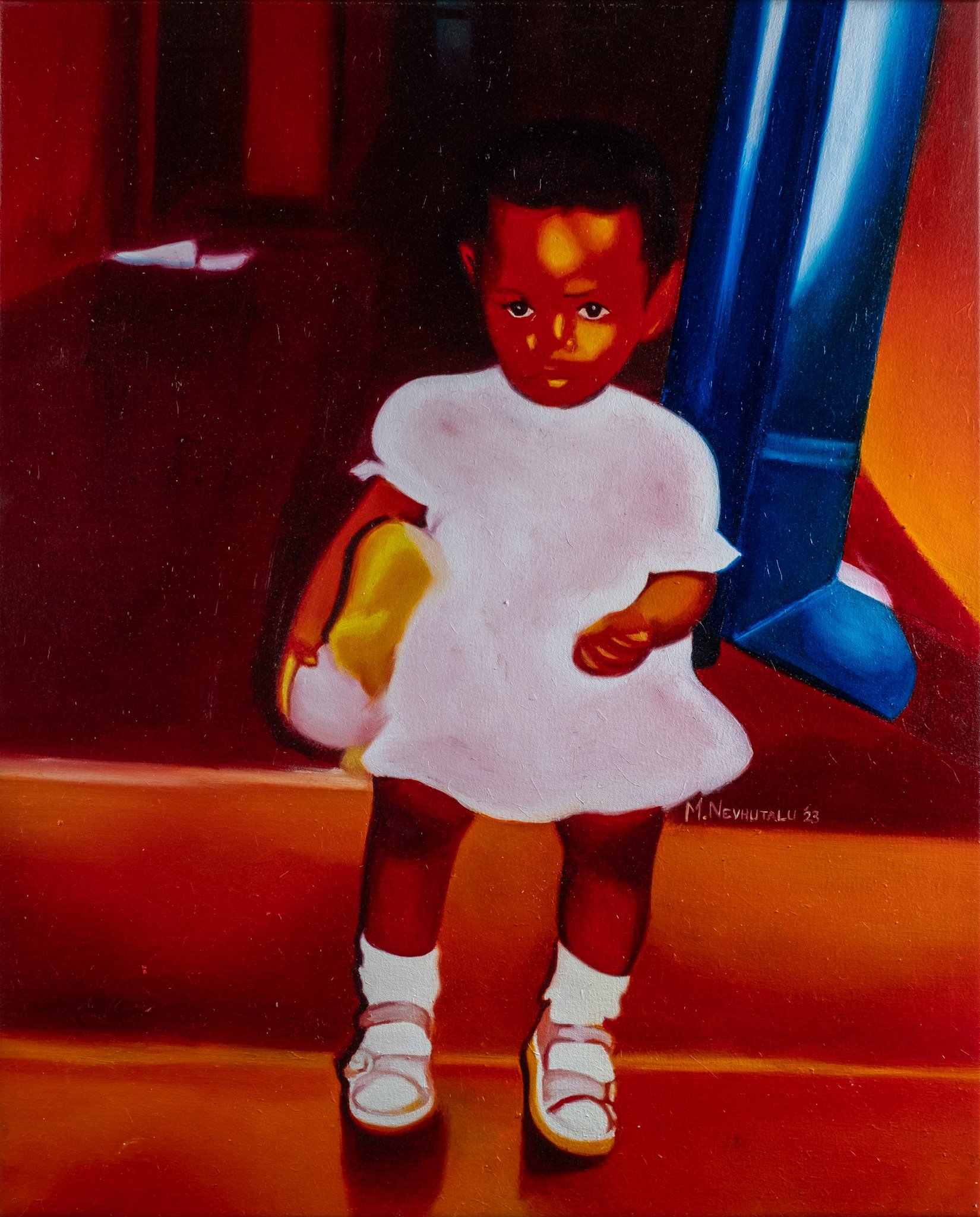

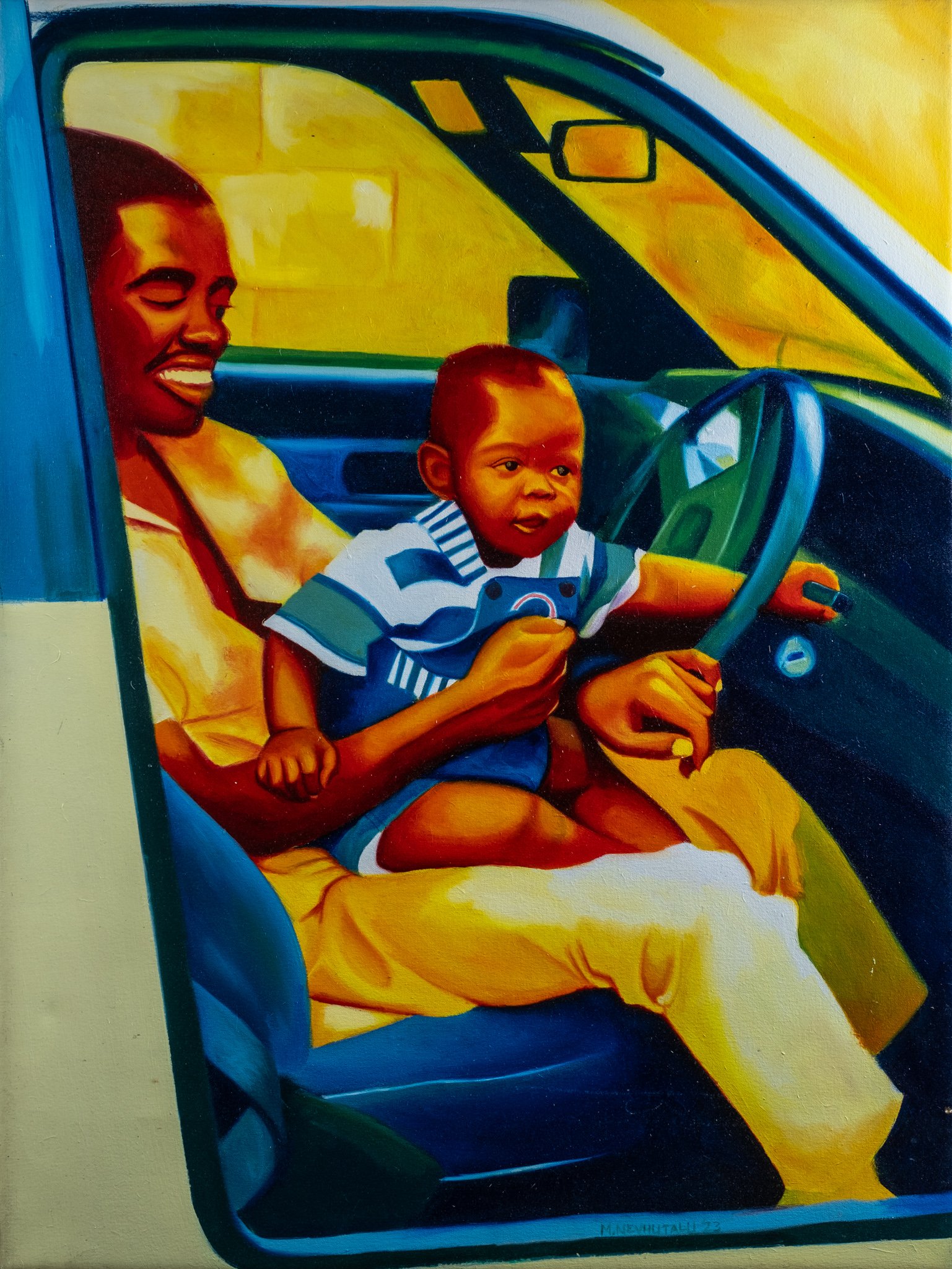

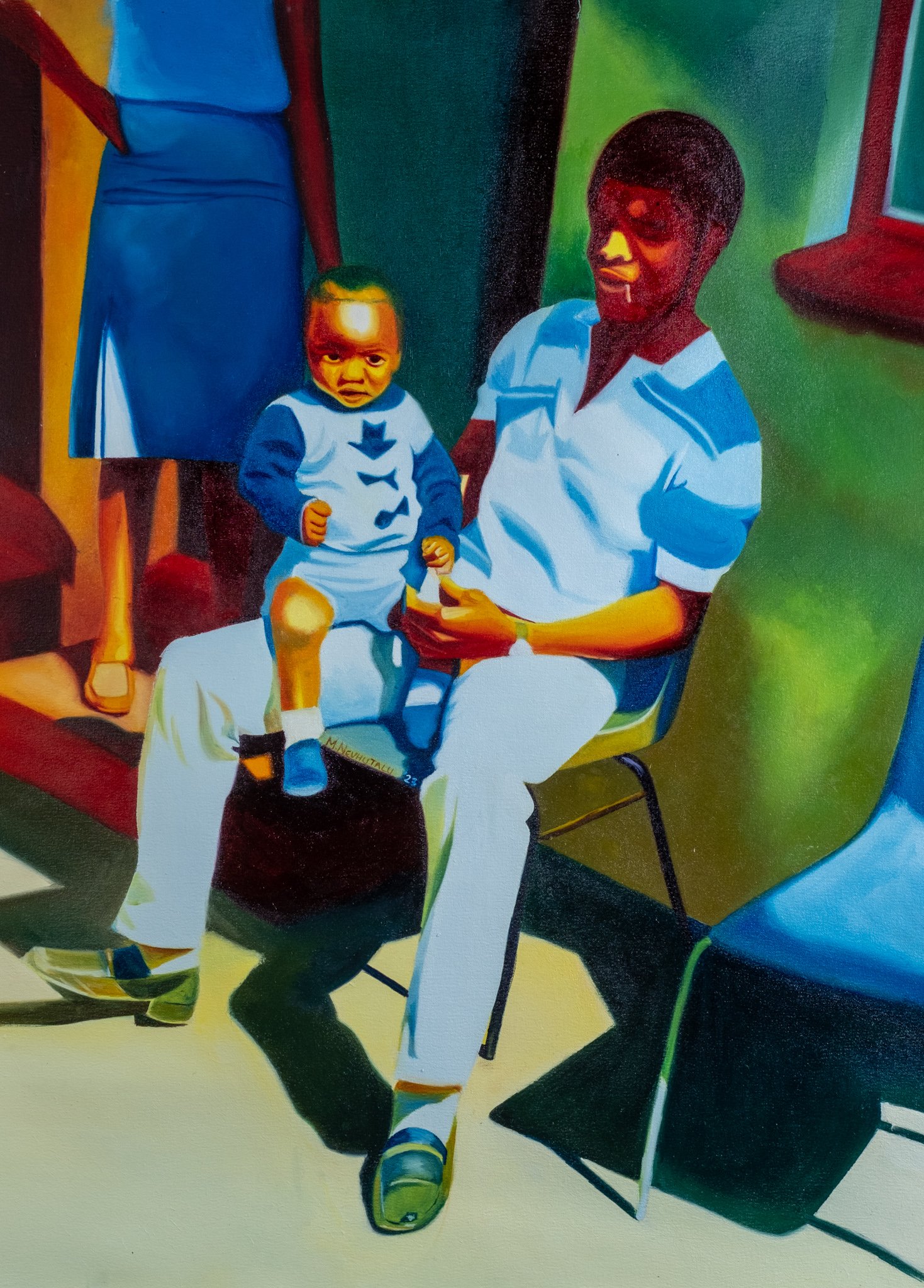

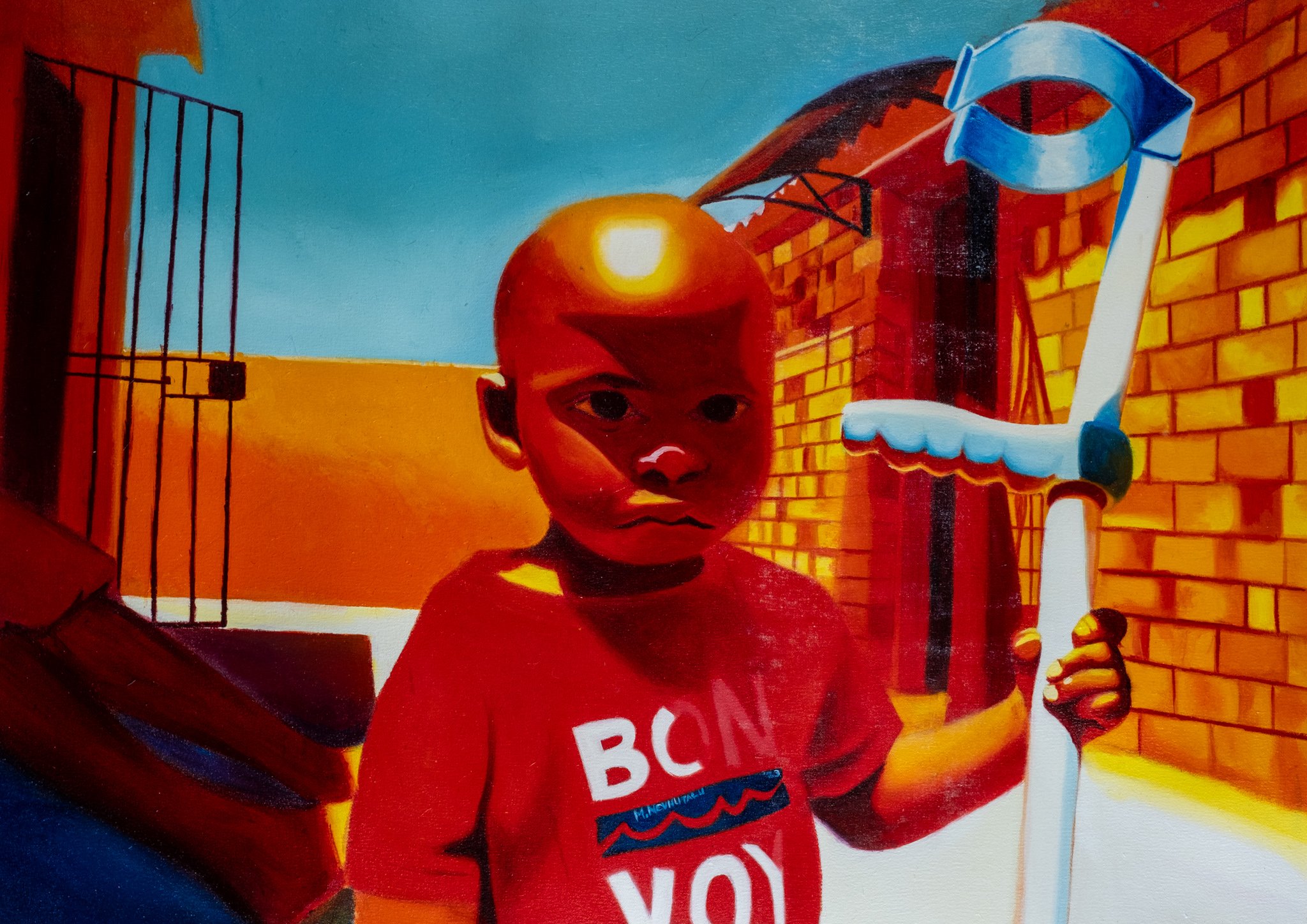

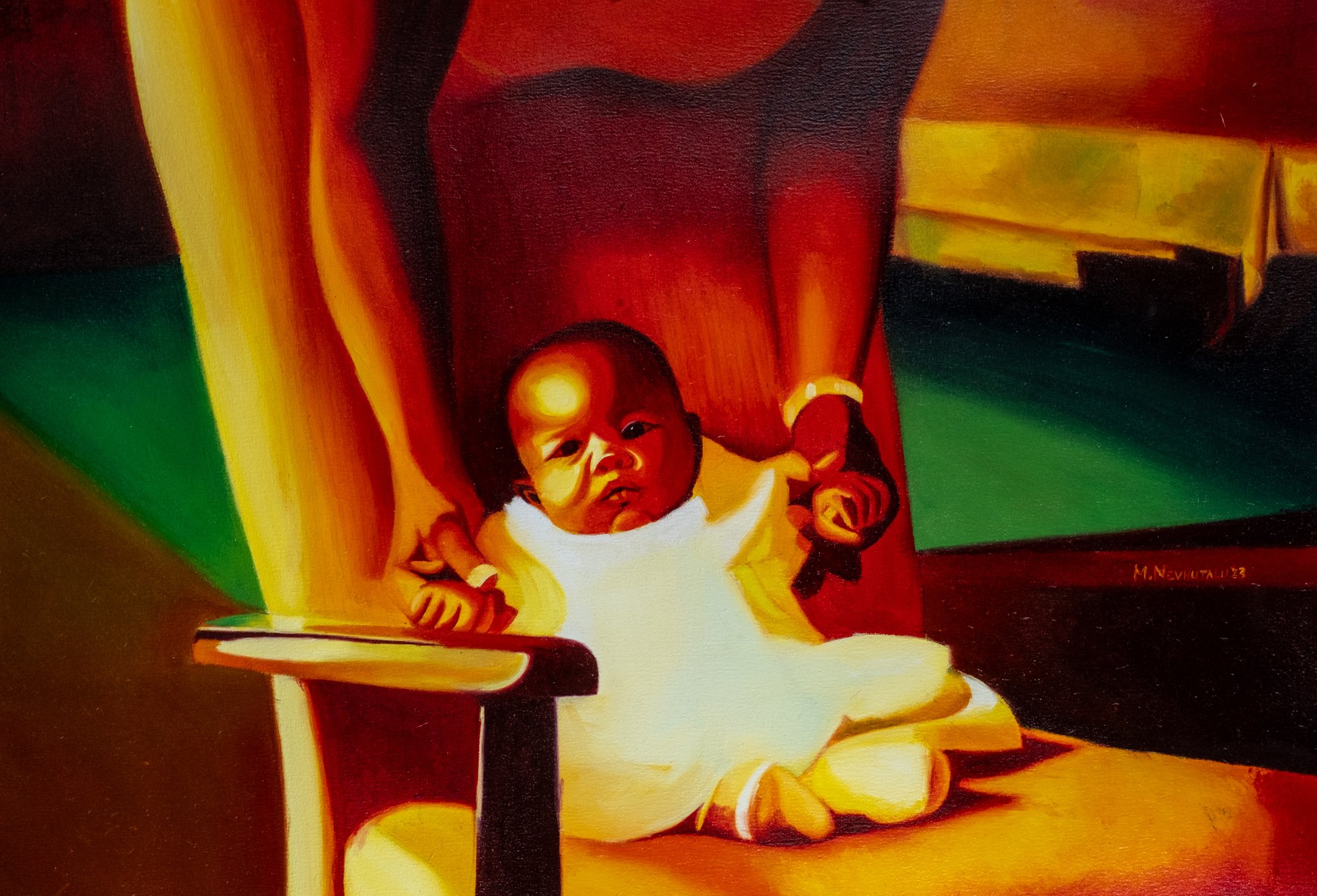

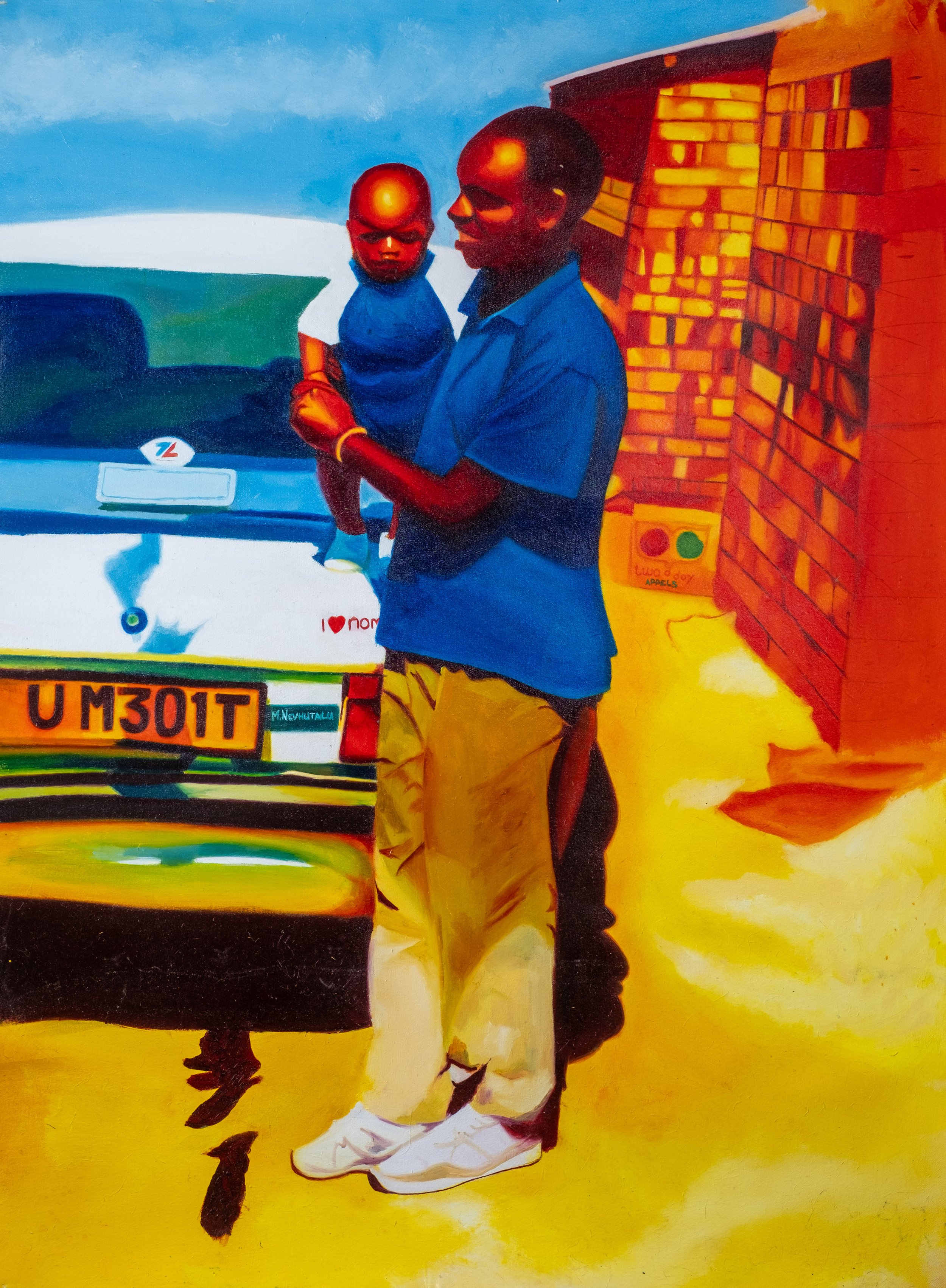

Titled Hayani, the exhibition unmasks the question "where are you from?" to reveal the ask, "whom are you from?" Unpacking nurture, it documents Nevhutalu's study of children centred parts of his family archive. "When I started working with the archives that my family kept all of these years: one of the things I noticed was there were a lot of photos with children in them," explains the artist. Whether shot in his mother, grandmother or aunts' houses, looking through the photographs brought about the realisation that he considers all of those places home because of the consistent presence of parental intervention.

“It’s something I hadn’t really dived into yet: those questions of what happened when I was growing up.” A question Nevhutalu poses to himself in addition to the public, concluding the body of work highlighted the absence of men in his configurations of home. “Why did I paint women more than men? And don’t get me wrong, my dad and uncles were there. But why don’t I have memories I attach to the men that were there when I was growing up?” Perhaps a decision informed by what was in the family archive, Nevhutalu explains the process behind his reference choices. “When I am interested in a photograph, I find out what it is about. I look for photographs with stories.” A task that sees Nevhutalu gathering primary or secondary witness accounts, his decision seems to be linked to those willing to recall what was. An opportunity to resolve what could not be in childhoods, Hayani also acknowledges the opportunity to expand what and how home is in the present.

Resembling water damaged photographs or observing a scene with blurred sight, in Hayani Nevhutalu’s signature of softening facial features beyond recognition has a two-fold function. Materialising the unreliable and diminishing nature of memories, Nevhutalu acknowledges the prevalence of dismissal when we remember. But obscure enough to be anybody, the style serves as an invitation for audiences to project representations that match their needs.

A relationship that has its origin in polyamory, Nevhatalu's commitment to painting was once parallel to one he had with printmaking. "When I got to my second year, I majored in printmaking and painting." Too stylistic and without the layered depth he needed for his current visual language, where details "trigger memories" Nevhutalu focused his efforts on developing his painting prowess. "It was frustrating, labour intensive and it needed a lot of patience but I enjoyed it."

Although subtle, the concept of play is a thin (yet robust) thread running through Nevhutalu's work. Suggested more than it is asserted, its occurrence resurfaces in different parts of his practice. In his process, it is research without expectation. Sensitive and responsive, Nevhutalu gives into the urge to digress into portrait making without being bound by concerns of output. In his style, it is a game of fabulation where in resisting the urge to paint the photographs he references realistically, he makes scenes of memories as he wants to remember them. In his thematic references, it is childhood memories of toy cars and spinning tops. In his presentation it is a treasure hunt where he invites audiences to gather puzzle pieces that tell a cohesive prose. He agrees. Once an obligation, on his practice, Nevhutalu says he has "learned to enjoy it... fun is in the forefront." A term often reserved in reference to children, playing involves the intentional act of engaging in an activity for the purpose of enjoyment. Stratified: play can also be understood as pointing to an act that has no practical purpose. And perhaps that is where to draw the line where Nevhutalu's practice is concerned, considering how play is how Nevhutalu’s process speaks back to him diving into formative year in Hayani.

Although what Hayani seeks is focused on the social construct of home, Nevhutalu offers the audience spatial resonance through the recurrence of brick walls, and concrete stoeps, freshly polished with Cobra wax, leading to door frames in a shade of red that matches the house's landing. Creating an effect often associated with installation, this inundation through repetition becomes a trigger. "It is to bring people into the paintings. Instead of being a snapshot that you can put down and not spend time with, I hope it allows you to step into that space where you engage with more than just your eyes."

To go back to the idea of locating home institutionally, while negotiating displacement against ventures of belonging, Nevhutalu's Hayani is a break from perpetual and often disappointing mediations that come with making or sustaining a home. Concluding a year marked by what felt like an international embrace of delusion, the exhibition’s stance presents a productive alternative to our naturalised apathy.